skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Is homosexuality common at boarding school?The school I attended was a co-educational school. That is the boys and girls were in the same lessons. The only difference was they were in different dormitories and sports were single sex.So place yourself in the shoes of a young child far from home. With nobody to cuddle them when they are sad or hurt. What happens - well these children have a few options.(1) Crush any desire for affection and touch.(2) Seek this from other children.Many of us, who have attended boarding school from a young age, learn (1) and we will usually have gone through (2), been thoroughly humiliated then learn to do (1).Bearing in mind that dormitories are single sex I think this answers the question of where (2) comes from.Credit: http://iwasatboardingschool.blogspot.com/2005/06/is-homosexuality-common-at-boarding.html

Is homosexuality common at boarding school?The school I attended was a co-educational school. That is the boys and girls were in the same lessons. The only difference was they were in different dormitories and sports were single sex.So place yourself in the shoes of a young child far from home. With nobody to cuddle them when they are sad or hurt. What happens - well these children have a few options.(1) Crush any desire for affection and touch.(2) Seek this from other children.Many of us, who have attended boarding school from a young age, learn (1) and we will usually have gone through (2), been thoroughly humiliated then learn to do (1).Bearing in mind that dormitories are single sex I think this answers the question of where (2) comes from.Credit: http://iwasatboardingschool.blogspot.com/2005/06/is-homosexuality-common-at-boarding.html

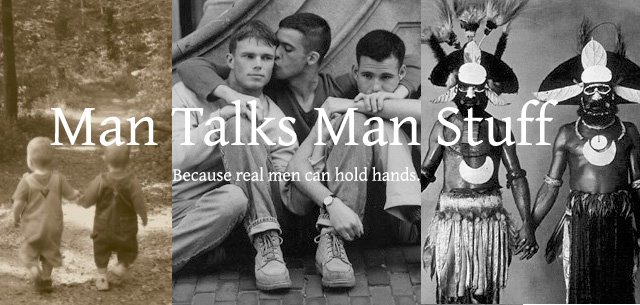

MTM: You know affection is needed when it calls. It would only seem irrational to NOT express, partake, provide or receive something so natural as intimacy. And you don't even need to call it homosexuality or anything.

At some point, one has to decide which is more important: (1) the expression of something good that it enriches the participants or (2) the illogical prejudice of some spectators that it destroys (1).

Review by J. Riga: The End of Gay (and the death of heterosexuality) by Bert Archer [Doubleday Canada, 1999]

Review by J. Riga: The End of Gay (and the death of heterosexuality) by Bert Archer [Doubleday Canada, 1999]

I avoided this book for many months. It arrived in the mail from an ex who'd never read it. It had a black line across the bottom indicating it had been rescued from the obscurity of a remainder bin. The title, with its arrogant sense of finality, irritated me. Sexuality is such a sticky, shifting mess of a topic that to make grand pronouncements, especially of death and endings, suggested an author himself a little stiff. Yet, I was surprised to find that beneath the desperate marketing department title lay an optimistic label-breaking take on contemporary sexuality. The End of Gay, using a blend of self and social analysis, actually seeks to further blur lines and thwart attempts to keep sexuality in simplified identity-laden categories.Divided into three parts, the first is largely autobiographical or based on Archer's personal observations of others and serves to loosely introduce us to his thesis. He believes that we are moving away from gay-bi-straight categories and towards a sexual pluralism free of labels, a re-articulation of the time when sexuality was divorced from a person's identity. As Archer says, "I'm not just arguing labels, I'm arguing ontology, Being itself." For him and the people he uses as examples, the categories are useless. A Catholic college friend of Archer's once claimed, "Y'know, I could see myself doin' a guy. I mean, I'm not a fag or nuthin", but y'know, if I was totally horned up, sure." This random statement was the catalyst for Archer's questioning of the neat little identity categories we have made for ourselves and the often instantaneous presumption that people like his college friend are closeted gays in need of enlightenment. He goes on to interview a man named Rafe who picked up men in straight clubs as Renee. Rafe claimed that after bringing straight men home and revealing that he too was a man "he'd only ever been turned down twice out of dozens of pick-ups." Archer, through examples, argues that the sexual straitjacket binding action to identity is loosening. While second hand sexual stories hardly amount to anything definitive, especially the end of gay, Archer's account of his own sexual expansion did what it intended, made me reassess my flippant use of sexual categorization. We all have our own little stories. Just as Archer's college friend caused confusion when he stuck a toe out of the straight box, I knew a man assumed closeted because of his feminine mannerisms. Despite consistently displaying only a sexual interest in women and denying any in men, I waited for him to come out. He still hasn't. I failed to ask myself if sometimes there really is nothing to come out about and also why femininity is always equated with a gay identity.The second section of the book is a straightforward account of how sexual behavior and identity formation have coalesced since the 1800s into what we now know loosely as the Gay Movement. From the invention of 'homosexual' and 'heterosexual' in 1868 to today's Gay Day at Disneyland, Archer's historical presentation is lively and accessible, expanding on key events such as Oscar Wilde's trial or the Kinsey Report as opposed to theory. Cornerstone queer theorists such as Judith Butler or Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick don't make appearances. Archer also dispenses with the opaque language of academia and speaks like a well-read friend, though admittedly, his occasional "whatever" or "as far as I can tell" was a little too casual and undermined his authority as an expert. Archer concludes this section with a critique of the current Gay Movement's alleged desire to become a carbon copy of the straight community.The last section is the most interesting and the most challenging. Archer explores the lives of people who have made difficult decisions about their sexual identities, denying the categories they initially embraced or refusing outright to take up house in any. His final analysis is that "you can expand your sexual horizon, but I'm not so sure you can contract it." One analogy Archer uses is food, which is neither an original nor a very strong one. I'm sure we've all heard the wink-wink-nudge-nudge-don't-knock-it-'til-you've-tried-it line before and the food argument is just a dressed up version of this. Archer writes, "I was remembering what my mother told me about olives "you keep eating them, and soon you begin to enjoy them. An acquired taste. The implication is that certain pleasures are learned, are worked for. They are nonetheless pleasurable for being the product of effort." Suggesting we can retrain ourselves to have a sexual interest where there currently isn't one sounds perhaps possible, but like a lot of bloody work. Archer goes one step further than the I'll-try-anything-once school and suggests we have to apply to sex something akin to the gleeful relentlessness found in prepubescent movies about sports teams. Just keep on trying 'til you succeed! A dose of old fashioned practicality seems necessary. I'm all for sexual pluralism and believe that we should explore our bodies with the same wonder we do the world. Yet the amount of time it would likely take for me to (possibly) expand my sexual preferences in any sincere, meaningful way seems like far too much of a commitment. Using his tired analogy, why eat jar after jar of olives when you're surrounded by food your already like? For some this type of sexual exploration is a meaningful pursuit, but I think the average person to whom this book is clearly directed will see it as a niche hobby along the lines of trekking to the North Pole for fun. Most people are too busy trying to find decent people of the gender or type they're already interested in to be flinging themselves at a vagina when all they want is a penis, or vice versa. For this reason, Archer's theory seems realistic only if reigned in a bit. We are moving, though at times painfully slowly, towards a greater degree of comfort and freedom with sexuality and a dispersal of the stigma attached to non-heterosexual sex acts, but these movements are counteracted by others. For example, the current media barrage of mostly stereotypical portrayals of gays, especially men, is still keeping homosexual sex acts tightly cinched to an identity, one narrowly based on marketable points; sex (Queer as Folk) and fashion (Queer Eye for the Straight Guy).One day we may dismantle homo and hetero categories, but with gay marriage as one of the hottest political issues today it's hard to believe that 'gay' is being surpassed as a functioning category for some. Not until all or most political aspects of the straight-gay dichotomy are equalized will people turn their full attention to redefining the boxes. Archer's analysis is inspiring but premature. Gay may be aging rapidly, but it's not yet on its last legs.

Credit: http://www.geocities.com/tokyocow/endofgay1.html by J. Riga